Microtubules and Filaments

The cytoskeleton is a structure that helps cells maintain their shape and internal organization, and it also provides mechanical support that enables cells to carry out essential functions like division and movement. There is no single cytoskeletal component. Rather, several different components work together to form the cytoskeleton.

What Is the Cytoskeleton Made Of?

What Do Microtubules Do?

Microtubules tend to grow out from the centrosome to the plasma membrane. In nondividing cells, microtubule networks radiate out from the centrosome to provide the basic organization of the cytoplasm, including the positioning of organelles.

What Do Actin Filaments Do?

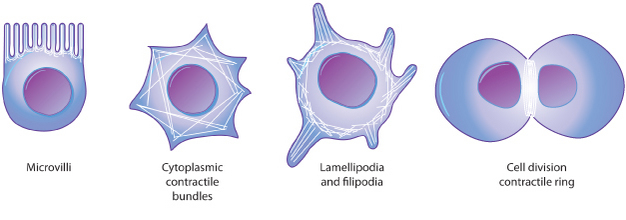

In many types of cells, networks of actin filaments are found beneath the cell cortex, which is the meshwork of membrane-associated proteins that supports and strengthens the plasma membrane. Such networks allow cells to hold — and move — specialized shapes, such as the brush border of microvilli. Actin filaments are also involved in cytokinesis and cell movement (Figure 3).

What Do Intermediate Filaments Do?

Intermediate filaments come in several types, but they are generally strong and ropelike. Their functions are primarily mechanical and, as a class, intermediate filaments are less dynamic than actin filaments or microtubules. Intermediate filaments commonly work in tandem with microtubules, providing strength and support for the fragile tubulin structures.

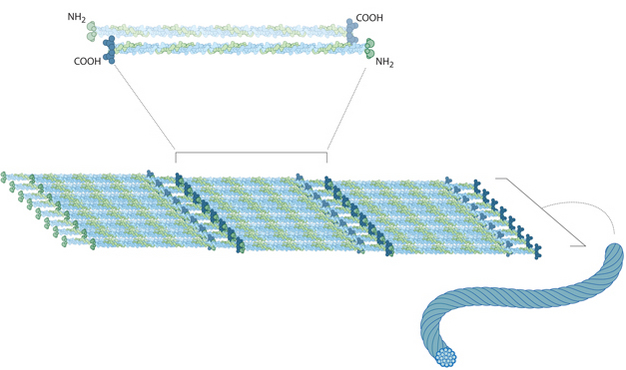

All cells have intermediate filaments, but the protein subunits of these structures vary. Some cells have multiple types of intermediate filaments, and some intermediate filaments are associated with specific cell types. For example, neurofilaments are found specifically in neurons (most prominently in the long axons of these cells), desmin filaments are found specifically in muscle cells, and keratins are found specifically in epithelial cells. Other intermediate filaments are distributed more widely. For example, vimentin filaments are found in a broad range of cell types and frequently colocalize with microtubules. Similarly, lamins are found in all cell types, where they form a meshwork that reinforces the inside of the nuclear membrane. Note that intermediate filaments are not polar in the way that actin or tubulin are (Figure 4).

How Do Cells Move?

Cytoskeletal filaments provide the basis for cell movement. For instance, cilia and (eukaryotic) flagella move as a result of microtubules sliding along each other. In fact, cross sections of these tail-like cellular extensions show organized arrays of microtubules.

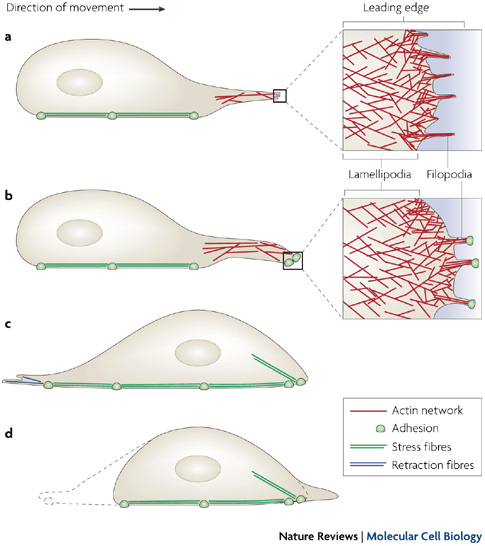

Other cell movements, such as the pinching off of the cell membrane in the final step of cell division (also known as cytokinesis) are produced by the contractile capacity of actin filament networks. Actin filaments are extremely dynamic and can rapidly form and disassemble. In fact, this dynamic action underlies the crawling behavior of cells such as amoebae. At the leading edge of a moving cell, actin filaments are rapidly polymerizing; at its rear edge, they are quickly depolymerizing (Figure 5). A large number of other proteins participate in actin assembly and disassembly as well.

Conclusion

eBooks

This page appears in the following eBook